EdSource journalists spent more than a year acquiring public records from law enforcement across California to document policing in K-12 schools. The project — a seemingly impossible undertaking due to barriers to public information — came at a time when communities were debating anew the role of armed officers in schools. (Graphics by EdSource. Photo: halbergman/istockphoto)

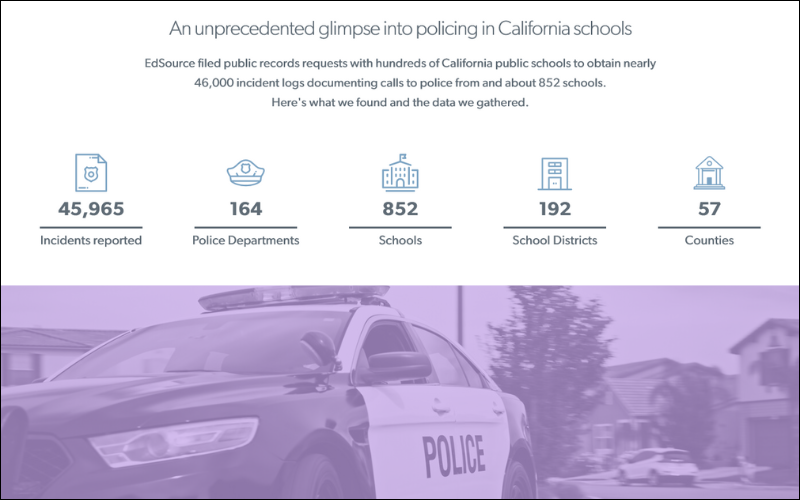

The nonprofit newsroom EdSource filed public records requests with hundreds of California police departments to obtain nearly 46,000 incident logs documenting calls to police from and about 852 schools. The resulting project, “Calling the Cops”, led by reporters Thomas Peele and Daniel J. Willis, is an unprecedented look at policing in our schools.

Peele, a Pulitzer Prize winning reporter and a member of the Freedom of Information Committee of the Society of Professional Journalists’ Northern California Chapter, shares lessons learned from this project and his decades of document-driven investigations.

Q: What are some of the key findings of “Calling the Cops”?

A: We documented an overwhelming police presence in schools across the state on a daily basis involving both officers assigned to schools by local law enforcement agencies, and responses to 911 calls. The records showed that 32% of calls reported a serious matter requiring police attention. Of the serious calls, 35% involved violence. We also found a great deal of alleged crimes that had never been made public, including an attempted murder, gun fire, and sexual misconduct.

The records also showed calls that involved a questionable use of police resources, such as a squirrel with an injured leg, a burned English muffin, and 2,824 ringing burglar alarms.

Q: Where did the idea for the project come from?

A: I have often tried to broadly document what seems to be un-documentable by collecting vast amounts of data from across a spectrum of public agencies. Having been long curious about both incidents where school administrators call police and how police respond, I wanted to try this technique on school policing by collecting a large sampling of records from police across California.

Q: The project seems undoable given the limits on public access in California.

A: Yes, we sort of faced nearly a triple level of blockage on this. With limited exceptions, police in California have very wide discretion to provide nothing under the California Public Records Act, largely because of the investigatory records exemption,* which is very broad and almost never expires. Additionally, schools are subject to educational privacy rules, so what happens in them is often secret under the law. And the arrests and prosecution of juveniles are, understandably, typically sealed* from public view. So there was really only one way to get at what we were doing, and that was a backdoor approach of going to police departments and asking for records of the calls they received from schools from 911 or assignment of police resource officers and what the police response was to those matters. That was a very significant undertaking with the Public Records Act that was 13 months in the making because it was a very uphill battle to gather the records. *See FAC Explainers for more information.

Q: What kinds of documents did you ultimately request and find most useful?

A: We requested records of calls for service “from and about” hundreds of schools. For the handful of police departments operated by school districts, we requested all calls for service involving those departments. We were able to capture the date, time and nature of calls, at a minimum. While some police departments gave us scant information, others provided full dispatch narratives rich with details.

Q: What were the barriers you experienced in accessing relevant records?

A: As usual with requests under the California Public Records Act, there were often long delays in both receiving legitimate 10-day determinations about the requested records and their production. It is frustrating when an agency sends what is basically an acknowledgement of a request but does not explain what records it has and when those records will be produced. It is clear from these requests that police staff are not well trained in the act’s basic requirements. This project was another example of the need for the CRPA to be modernized and given teeth and an enforcement mechanism.

Q: What advice do you have for journalists looking to launch large records-acquisition projects like this?

A: Plan and organize.

I want complete control over my requests, so I don’t use Muck Rock, although others prefer it. I suggest people do written requests on an email address they manage because of tools for accountability, such as read receipts. Under the California Public Records Act, an agency cannot mandate that you use an automated system to make a request. Always get it in front of a human being. What they do with it from then on is out of the requester’s control, but by sending it to a human you have a human to hold accountable for how the request is handled.

Remember that the agency is subordinate to the requesting party, not the other way around. Hound the agency if needed. You are not there to make friends.

When collecting police records, I make it a practice to send requests to city managers, not police directly. By involving civilian oversight of the police, and ensuring that personnel outside of the police department know of the request, I think this can help make sure my request is not ignored. Keep the city manager copied on all communications. Also, limit all communications about the request to writing. Don’t call or otherwise speak to officials about the request. Keep interviews separate. Maintain the written record. It’s the first thing a lawyer is going to ask you for should it come to that.

Know the law. If you don’t receive a determination within 10 days as the law requires, demand it. If needed, copy additional officials on the correspondence, including elected officials.

I also suggest people track requests and responses by spreadsheet and challenge exemptions and redactions.

Q: Some records requesters will push for disclosure of public records on a rolling basis as an alternative to getting no records at all or nothing for months or worse. Is there ever a scenario when you would welcome a rolling production of records?

A: No. It’s an invitation for a never-ending trickle of records, often with no end in sight. One of the PRA’s biggest flaws is the lack of production deadlines. But if the determination process is followed, the agency should know within 10 days what responsive records it intendends produce and when.

Q: Final advice for journalists in particular?

A: Be a pain in the ass. Make it clear that an agency’s response to a PRA request may be newsworthy and that you may report on it. A potential story on an agency’s inability to produce records may force bureaucrats to hurry the hell up.

READ MORE

- Calling the Cops: Policing California Schools

- Visit the Database

- Podcast: Why California schools call the police

FAC RESOURCES

- Fee Legal Hotline

- California Public Records Act request template

- FAQs on the California Public Records Act

- Explainers on commonly asked questions about public access law