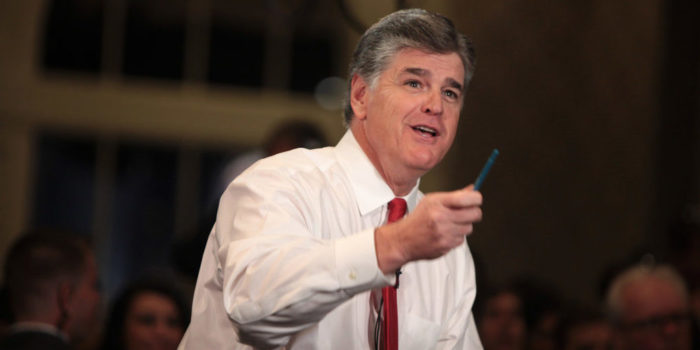

BY DAVID SNYDER — When a federal judge ordered President Donald Trump’s personal attorney, Michael Cohen, to disclose in open court the fact that he considers Fox News host Sean Hannity a client, the Trump Era outrage-industrial complex shifted into high gear.

BY DAVID SNYDER — When a federal judge ordered President Donald Trump’s personal attorney, Michael Cohen, to disclose in open court the fact that he considers Fox News host Sean Hannity a client, the Trump Era outrage-industrial complex shifted into high gear.

Seeing evidence of some nefarious Deep State plot to embarrass Trump and his confederates, conservative commentators criticized Judge Kimba Wood for requiring the information to be disclosed, while many on the Left reacted with a sort of feverish glee at the revelation, which they took to be more proof that the Trump administration is a shambolic, incestuous circus.

But for all the outrage and conspiracy mongering, everyone seems to have missed the most important point in all of this: Of course Judge Wood ordered Hannity’s name disclosed—she really had no choice under the First Amendment.

Under well-established law, a party that wants to deny public access to records submitted in most types of court proceedings must justify that request by showing the sealing of documents is “strictly and inescapably necessary” in order to protect a “compelling government interest.”

In layman’s terms, that means it should be very difficult to do what Cohen’s lawyers wanted to do—submit secret information to a court. Everyone has a right, under the United States Constitution, to see what happens in most criminal (and civil) court proceedings. There are some narrow exceptions, such as trade secrets, information that implicates national security concerns, and—relevant to the Cohen hearing—attorney-client privileged communications.

However, with some exceptions not applicable in this case, the mere identity of a client is not subject to the attorney-client privilege, which only protects the content of communications between attorney and client relating to legal representation. Cohen’s lawyers appear to have made a half-hearted argument that Hannity’s identity was subject to the attorney-client privilege, and they also claimed Hannity’s name should remain under wraps because simply be he asked Cohen not to disclose it. More ridiculous was their suggestion that name shouldn’t be disclosed essentially because it would embarrass Hannity–that “no one would want to be associated with” Michael Cohen as a client.

None of these reasons come close to meeting the “strictly and inescapably necessary” standard nor do they show any “compelling government interest ” in keeping them secret.

And yet. In the April 16 hearing where Hannity’s name was disclosed, Judge Wood appeared ready to allow the name to be submitted under seal when attorney Robert Balin, representing various media outlets, spoke up. He articulated the principles I’ve discussed above and, to her credit, Judge Wood ordered the name disclosed.

It’s worrisome that the public right of access, sacrosanct under the First Amendment, is so tenuous—so dependent on a lawyer showing up and making the case. Yet here, the system worked—at least as far as the court system goes.

The same can’t be said for the media analysis, such as it was, that followed. Following their usual patterns, the partisan tribes beat their partisan drums, twisting the law to satisfy political bloodlust. While there may be valid, partisan reasons to either cheer or criticize the revelation, the legal reasons for the disclosure were clear—and decidedly non-partisan.

And yet. Writing in the National Review, former Assistant U.S. Attorney Andrew McCarthy deemed Judge Wood’s decision “outrageous,” presenting the issue for Judge Wood to decide as whether there was “a reason for Hannity’s name to be revealed publicly.” This is the wrong question. Indeed, it’s the inverse of the question that the First Amendment required Judge Wood to ask, which is: “is there a very good reason that Hannity’s name must not be revealed publicly?”

McCarthy may be correct as a general matter that “judicially endorsed standards” prohibit “identifying uncharged persons in legal proceedings attendant to criminal investigations.” But once Cohen’s lawyers sought to submit the name of an “uncharged person,” i.e., Hannity, to a court in an open court proceeding, the Constitution trumps these unspecified “judicially endorsed standards.” And the Constitution, as interpreted by numerous courts, could not be more clear: submitting information under seal requires a showing that secrecy is “strictly and inescapably necessary” in order to protect a “compelling government interest.” That standard clearly was not met.

The flaw in McCarthy’s reasoning stems from his reversal of the presumptions established by the First Amendment. McCarthy allowed that “if the public has a legal right to know a piece of information, the fact that the information is likely to embarrass someone is not sufficient cause to suppress it” (emphasis original). However, the First Amendment does not first ask whether “the public has a legal right to know a piece of information.” Instead, it requires courts to presume that the public has a right to know.

As the Supreme Court held in 1982 in Globe Newspaper Co v. Superior Court, “a presumption of openness inheres in the very nature of a criminal trial under our system of justice.” Thus, the burden was on Cohen’s lawyers to overcome that presumption. Embarassing a television host does not rise to the level. If the host were not named Hannity, and if the lawyer at issue did not have Trump as a client, it’s unlikely anyone would have cast much doubt on Judge Wood’s ruling.

That said, if the Cohen-Trump-Hannity trifecta were not at issue that day—and therefore no media lawyer had been present to champion the First Amendment—the judge might have made the wrong call.

David Snyder, a lawyer and journalist, is executive director of the First Amendment Coalition. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the FAC Board of Directors.